Joe Wallig, left, a mechanical engineering associate, and Brian Reynolds, a mechanical technician, work on the final assembly of the LCLS-II injector gun in a specially designed clean room at Berkeley Lab in August. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

Every powerful X-ray pulse produced for experiments at a next-generation laser project, now under construction, will start with a “spark” – a burst of electrons emitted when a pulse of ultraviolet light strikes a 1-millimeter-wide spot on a specially coated surface.

A team at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) designed and built a unique version of a device, called an injector gun, that can produce a steady stream of these electron bunches that will ultimately be used to produce brilliant X-ray laser pulses at a rapid-fire rate of up to 1 million per second.

The injector arrived Jan. 22 at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (SLAC) in Menlo Park, California, the site of the Linac Coherent Light Source II (LCLS-II), an X-ray free-electron laser project.

Getting up to speed

The injector will be one of the first operating pieces of the new X-ray laser. Initial testing of the injector will begin shortly after its installation.

The injector will feed electron bunches into a superconducting particle accelerator that must be supercooled to extremely low temperatures to conduct electricity with nearly zero loss. The accelerated electron bunches will then be used to produce X-ray laser pulses.

Scientists will employ the X-ray pulses to explore the interaction of light and matter in new ways, producing sequences of snapshots that can create atomic- and molecular-scale “movies,” for example, to illuminate chemical changes, magnetic effects, and other phenomena that occur in just quadrillionths (million-billionths) of a second.

This new laser will complement experiments at SLAC’s existing X-ray laser, which launched in 2009 and fires up to 120 X-ray pulses per second. That laser will also be upgraded as a part of the LCLS-II project.

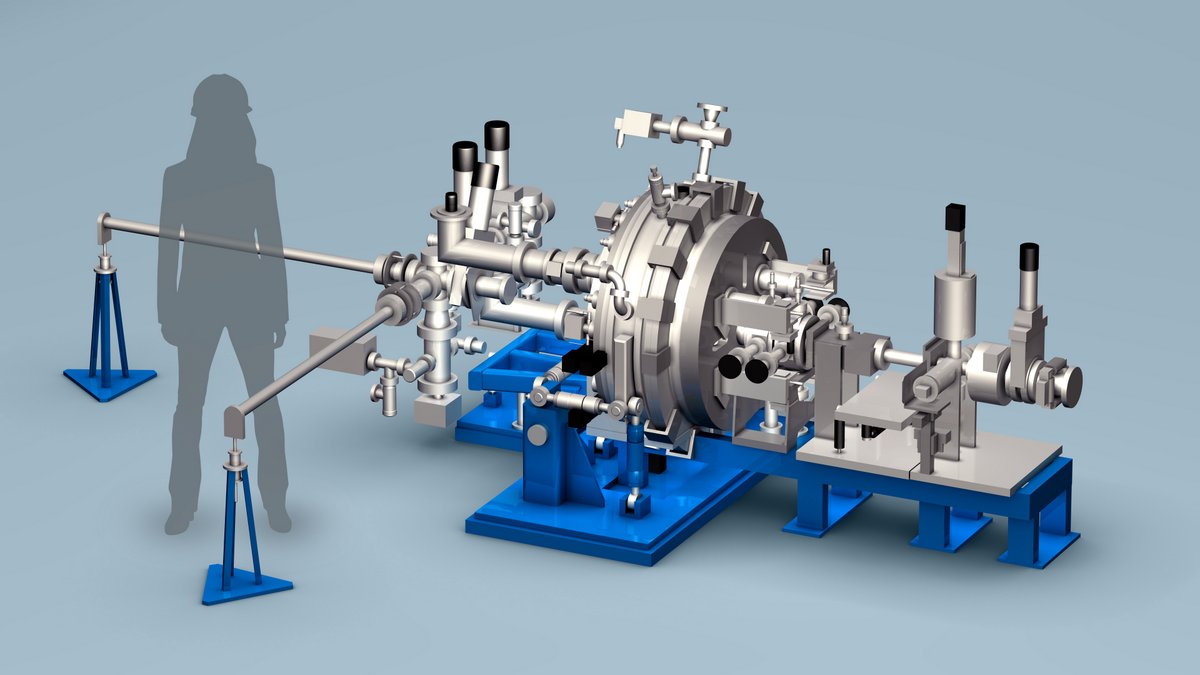

A rendering of the completed injector gun and related beam line equipment. (Credit: Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

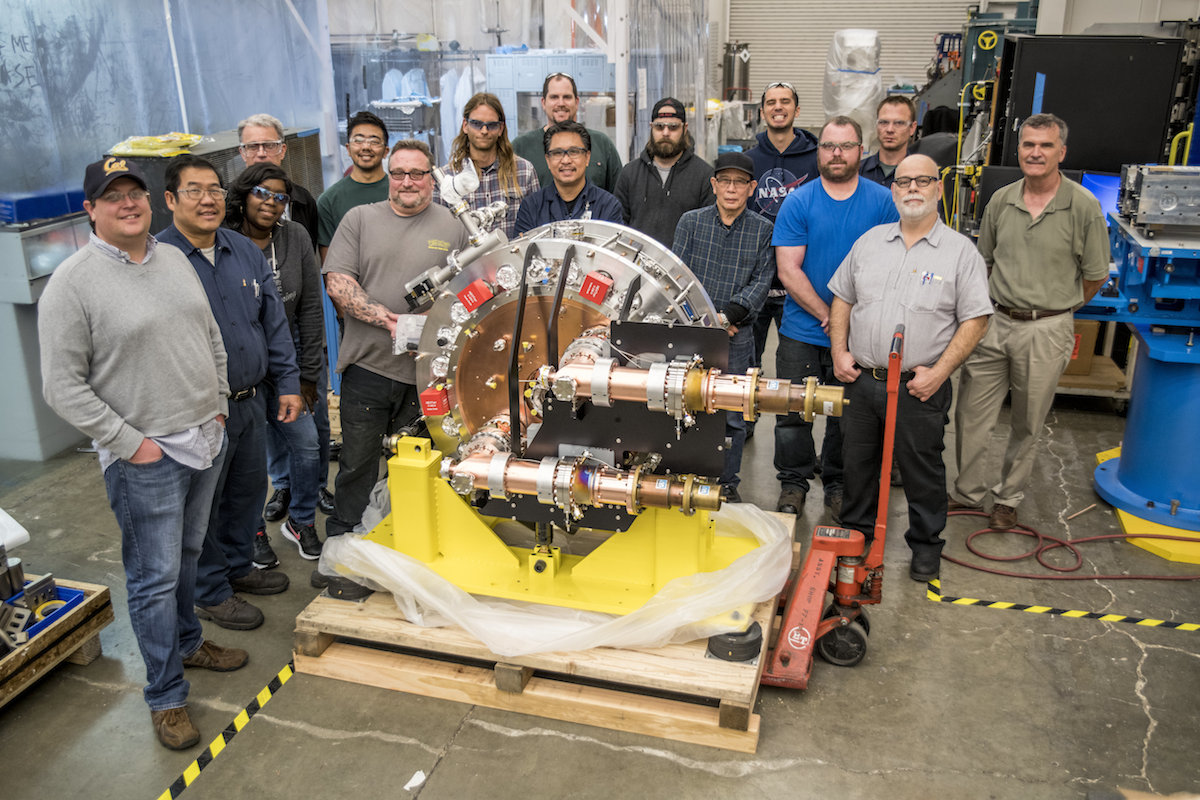

The injector gun project teamed scientists from Berkeley Lab’s Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division with engineers and technologists from the Engineering Division in what Engineering Division Director Henrik von der Lippe described as “yet another success story from our longstanding partnership – (this was) a very challenging device to design and build.”

“The completion of the LCLS-II injector project is the culmination of more than three years of effort,” added Steve Virostek, a Berkeley Lab senior engineer who led the gun construction. The Berkeley Lab team included mechanical engineers, physicists, radio-frequency engineers, mechanical designers, fabrication shop personnel, and assembly technicians.

“Virtually everyone in the Lab’s main fabrication shop made vital contributions,” he added, in the areas of machining, welding, brazing, ultrahigh-vacuum cleaning, and precision measurements.

The injector source is one of Berkeley Lab’s major contributions to the LCLS-II project, and builds upon its expertise in similar electron gun designs, including the completion of a prototype gun. Almost a decade ago, Berkeley Lab researchers began building a prototype for the injector system in a beam-testing area at the Lab’s Advanced Light Source.

That successful effort, dubbed APEX (Advanced Photoinjector Experiment), produced a working injector that has since been repurposed for experiments that use its electron beam to study ultrafast processes at the atomic scale. Fernando Sannibale, Head of Accelerator Physics at the ALS, led the development of the prototype injector gun.

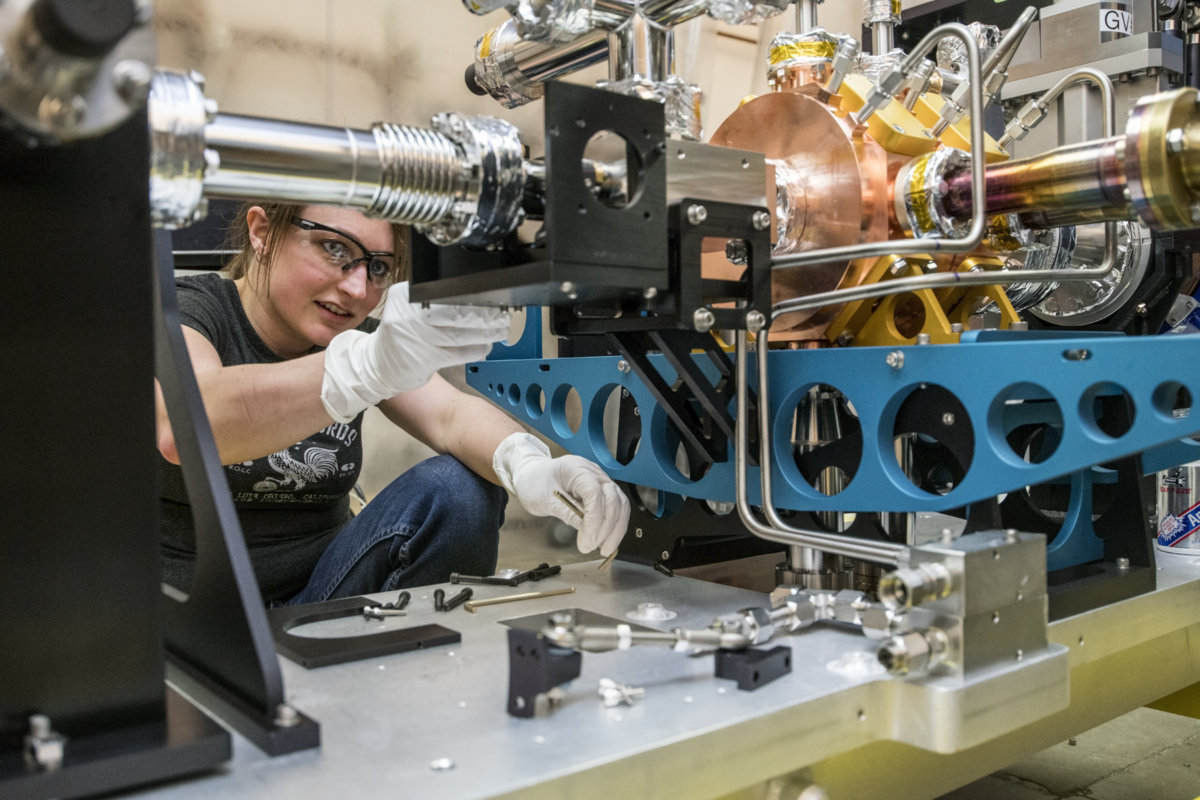

Krista Williams, a mechanical technician, works on the final assembly of LCLS-II injector components on Jan. 11. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

“This is a ringing affirmation of the importance of basic technology R&D,” said Wim Leemans, director of Berkeley Lab’s Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division. “We knew that the users at next-generation light sources would need photon beams with exquisite characteristics, which led to highly demanding electron-beam requirements. As LCLS-II was being defined, we had an excellent team already working on a source that could meet those requirements.”

The lessons learned with APEX inspired several design changes that are incorporated in the LCLS-II injector, such as an improved cooling system to prevent overheating and metal deformations, as well as innovative cleaning processes.

“We’re looking forward to continued collaboration with Berkeley Lab during commissioning of the gun,” said SLAC’s John Galayda, LCLS-II project director. “Though I am sure we will learn a lot during its first operation at SLAC, Berkeley Lab’s operating experience with APEX has put LCLS-II miles ahead on its way to achieving its performance and reliability objectives.”

Mike Dunne, LCLS director at SLAC, added, “The performance of the injector gun is a critical component that drives the overall operation of our X-ray laser facility, so we greatly look forward to seeing this system in operation at SLAC. The leap from 120 pulses per second to 1 million per second will be truly transformational for our science program.”

How it works

Like a battery, the injector has components called an anode and cathode. These components form a vacuum-sealed central copper chamber known as a radio-frequency accelerating cavity that sends out the electron bunches in a carefully controlled way.

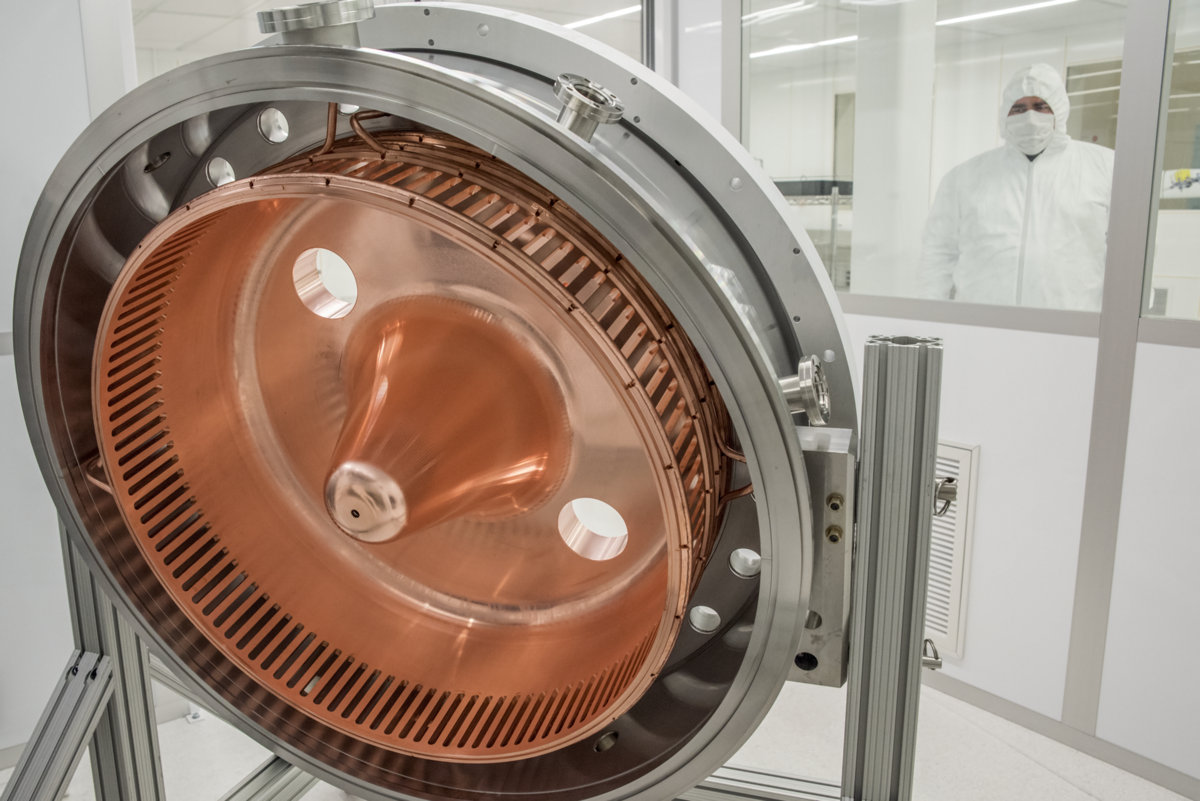

The cavity is precisely tuned to operate at very high frequencies and is ringed with an array of channels that allow it to be water-cooled, preventing overheating from the radio-frequency currents interacting with copper in the injector’s central cavity.

A copper cone structure inside the injector gun’s central cavity. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

A copper cone structure within its central cavity is tipped with a specially coated and polished slug of molybdenum known as a photocathode. Light from an infrared laser is converted to an ultraviolet (UV) frequency laser, and this UV light is steered by mirrors onto a small spot on the cathode that is coated with cesium telluride (Cs2Te), exciting the electrons.

These electrons are are formed into bunches and accelerated by the cavity, which will, in turn, connect to the superconducting accelerator. After this electron beam is accelerated to nearly the speed of light, it will be wiggled within a series of powerful magnetic structures called undulator segments, stimulating the electrons to emit X-ray light that is delivered to experiments.

Precision engineering and spotless cleaning

Besides the precision engineering that was essential for the injector, Berkeley Lab researchers also developed processes for eliminating contaminants from components through a painstaking polishing process and by blasting them with dry ice pellets.

The final cleaning and assembly of the injector’s most critical components was performed in filtered-air clean rooms by employees wearing full-body protective clothing to further reduce contaminants – the highest-purity clean room used in the final assembly is actually housed within a larger clean room at Berkeley Lab.

“The superconducting linear accelerator is extremely sensitive to particulates,” such as dust and other types of tiny particles, Virostek said. “Its accelerating cells can become non-usable, so we had to go through quite a few iterations of planning to clean and assemble our system with as few particulates as possible.”

Joe Wallig, a mechanical engineering associate, prepares a metal ring component of the injector gun for installation using a jet of high-purity dry ice in a clean room. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

The dry ice-based cleaning processes function like sandblasting, creating tiny explosions that cleanse the surface of components by ejecting contaminants. In one form of this cleaning process, Berkeley Lab technicians enlisted a specialized nozzle to jet a very thin stream of high-purity dry ice.

After assembly, the injector was vacuum-sealed and filled with nitrogen gas to stabilize it for shipment. The injector’s cathodes degrade over time, and the injector is equipped with a “suitcase” of cathodes, also under vacuum, that allows cathodes to be swapped out without the need to open up the device.

“Every time you open it up you risk contamination,” Virostek explained. Once all of the cathodes in a suitcase are used up, the suitcase must be replaced with a fresh set of cathodes.

The overall operation and tuning of the injector gun will be remotely controlled, and there is a variety of diagnostic equipment built into the injector to help ensure smooth running.

Even before the new injector is installed, Berkeley Lab has proposed to undertake a design study for a new injector that could generate electron bunches with more than double the output energy. This would enable higher-resolution X-ray-based images for certain types of experiments.

Berkeley Lab Contributions to LCLS-II

John Corlett, Berkeley Lab’s senior team leader, worked closely with the LCLS-II project managers at SLAC and with Berkeley Lab managers to bring the injector project to fruition.

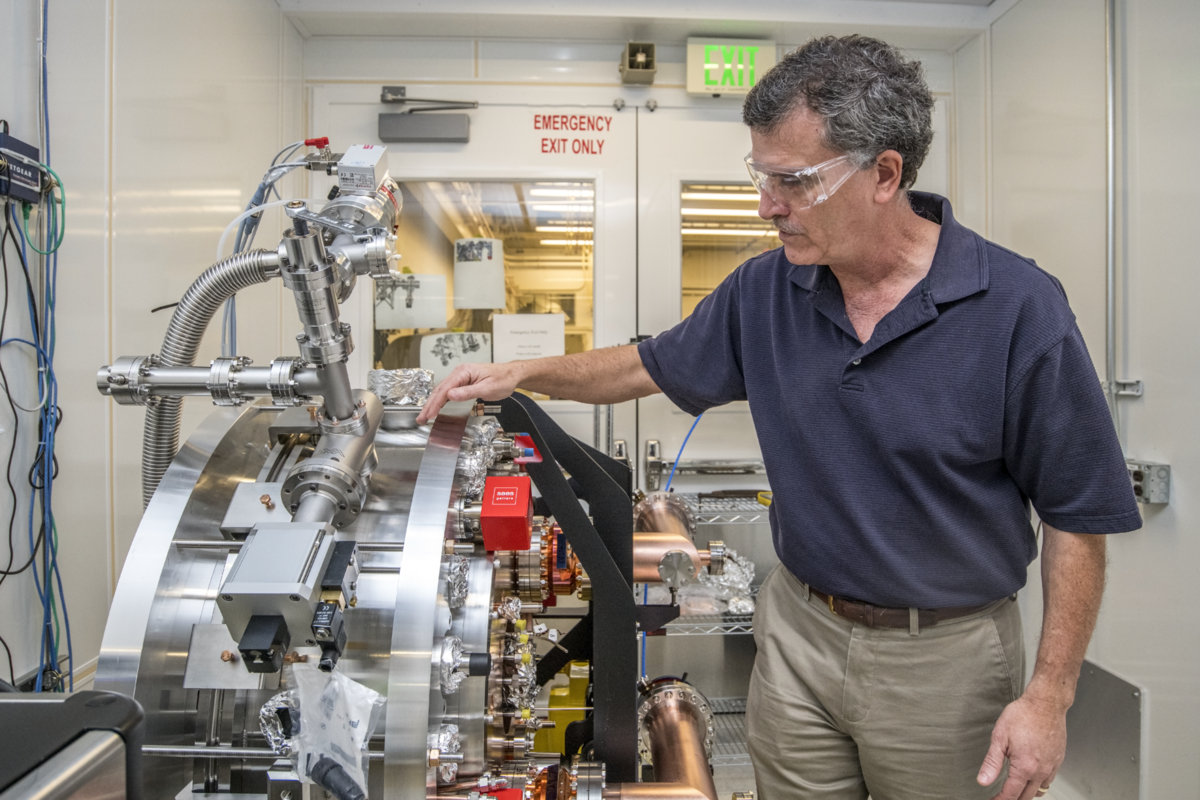

Steve Virostek, a senior engineer who led the injector gun’s construction, inspects the mounted injector prior to shipment. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

“In addition to the injector source, Berkeley Lab is also responsible for the undulator segments for both of the LCLS-II X-ray free-electron laser beamlines, for the accelerator physics modeling that will optimize their performance, and for technical leadership in the low-level radio-frequency controls systems that stabilize the superconducting linear accelerator fields,” Corlett noted.

James Symons, Berkeley Lab’s associate director for physical sciences, said, “The LCLS-II project has provided a tremendous example of how multiple laboratories can bring together their complementary strengths to benefit the broader scientific community. The capabilities of LCLS-II will lead to transformational understanding of chemical reactions, and I’m proud of our ability to contribute to this important national project.”

LCLS-II is being built at SLAC with major technical contributions from Argonne National Laboratory, Fermilab, Jefferson Lab, Berkeley Lab, and Cornell University. Construction of LCLS-II is supported by DOE’s Office of Science.

View more photos of the injector gun and related equipment: here and here.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.